uhlin—a senior from Eden Prairie, Minnesota, studying Speech, Language and Hearing Sciences in the College of Liberal Arts—will eventually apply what she’s learned in the program to her career. But Ruhlin is different in that she’s already taken what she learned from the classroom all the way to the Mayo Clinic after she set a chain of events in motion that led to the discovery of her father’s brain tumor.

In class, Ruhlin learned about parts of the ear, the importance of hearing aids and tumors like acoustic neuromas that can cause hearing loss. Meanwhile, her father, Joe, had struggled with worsening hearing loss for years—only talking on the phone on one side, not hearing anything said near his left ear—so Ruhlin urged him to set up an appointment with an audiologist.

“Once I started taking these classes, it put it more into perspective,” Rachel Ruhlin said. “My professor would talk about how many people have hearing loss, and if you don’t get hearing aids, your hearing will just get worse and worse. Finally, I texted my dad and I said, ‘We have to go.’ I didn’t really give him an option.”

Originally, the appointment was simply to test if Joe Ruhlin would be a candidate for hearing aids. He thought his worsening hearing was just a result of aging, but after Rachel explained the many social, emotional and psychological implications of hearing loss, he was persuaded.

Plus, Joe Ruhlin said, it would be interesting for his daughter to see a real hearing test, so he agreed to go.

“She strongly encouraged me to set up an appointment while she was home,” Joe Ruhlin said. “And I think she knew I would go with her, partly because it was going to be interesting for her to see up close what an audiology test looks like, what a hearing test would look like and participate in it and ask questions.”

At the first audiology appointment, it was no surprise to Ruhlin that her father’s hearing test indicated serious hearing loss on one side. The next step in the process was for Rachel’s father to visit an ear, nose and throat doctor, who would conduct a more comprehensive test, including ordering an MRI.

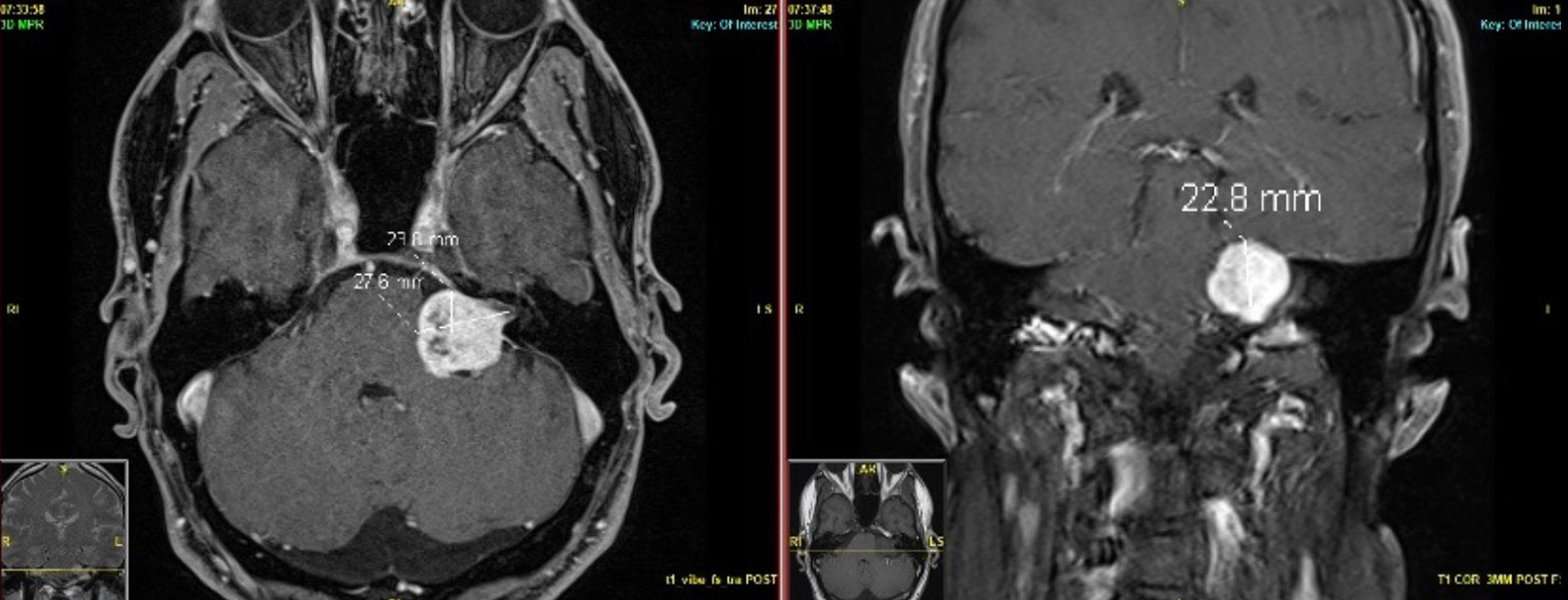

When the MRI results came back showing a large tumor, Rachel knew exactly what it was: an acoustic neuroma, an extremely rare, but serious brain tumor. It was one of the worst-case scenarios she was familiar with through her classes at Auburn.

In Auburn’s Speech, Language and Hearing Sciences, or SLHS, program, all students must take Professor Sridhar Krishnamurti’s audiology class, where they learn foundational knowledge about hearing loss.

“This class teaches them what the field is about, it’s our trademark class in audiology for undergraduates,” Krishnamurti said. “Very few people, like Rachel, take it to that next level where they translate it to help their family. This is the first time in 25 years that I’ve experienced a student affecting their family’s future.”

Because of that class, Ruhlin said she had a firm grasp on everything that was happening.

“When we went to the audiologist the first time, I knew exactly what was going on with his audiogram and how bad it was because I had seen audiograms in class all the time,” Ruhlin said. “Then we went to the surgeons, and they were talking about parts of the ear, and I’ve learned all those. Before surgery, I knew everything that was going on because we learned about this specific type of tumor in class. So, if I hadn’t had these classes, I definitely would’ve been a lot more confused and in the dark.”

An acoustic neuroma, also known as a vestibular schwannoma, is a benign tumor that grows in the cells surrounding the hearing and balance nerves. Common symptoms include hearing loss on one side, ringing in one ear, dizziness and facial numbness when the tumor gets large.

Acoustic neuromas are rare, affecting only about three people in 100,000, but are risky because of their proximity to the brain stem. Left untreated, they can grow large enough to compress the brain stem and become life-threatening.

“Even though it’s benign, having something growing inside your head is somewhat of a risk. And where this tumor arises, there’s a lot of important things, especially the brain stem, right next to it. So, as these tumors slowly enlarge, they can start to push on some critical structures,” Link said. “The other issue is that right with the hearing and balance nerve runs the facial nerves, which innervates all the muscles of facial expression. As the tumor gets bigger, the risk that the facial nerve will be injured or won’t work well after surgery goes up.”

The treatment options for a vestibular schwannoma include surgery, radiation and observation. Because of the size of Joe Ruhlin’s tumor, Link conducted a successful surgical removal on Feb. 16 at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

Because the tumor is so embedded in the hearing nerves, total hearing loss on the affected side is expected when a large tumor is removed. Link said patients also experience temporary balance issues and facial weakness following the surgery.

Link said while acoustic neuromas are rare, any hearing issues should be taken seriously.

“The great, great majority of the time, when people have unilateral hearing loss or unilateral ringing in the ear, it is not a tumor. But once again, it’s always worth getting it checked out,” Link said. “It’s been fascinating to me that so many people have hearing loss and refuse to get it checked out. It is a big issue for quality of life if you’re missing a lot of what’s going on around you. So, I think for all of our family members, we have to be vigilant and say if you’re not hearing well, you need to get it checked out.”

For a few months after the operation, Joe Ruhlin recovered from the surgery and slowly regained his balance, content with the knowledge that the tumor is completely removed and he is no longer at risk of further damage.

Ruhlin said he’s grateful his daughter had the knowledge to help guide him through the process.

“It means a lot that she helped me get through this,” Ruhlin said. “I’m very grateful that she pushed me to go see the doctor. It did take some encouragement, and she’s very good at encouraging me to do things. Daughters can be that way.

“So, I’m very grateful that she was in that audiology class at the time. She was talking to her audiology professors, and they were backing up what we were hearing, so it was very comforting to have her support.”

Throughout the process, Rachel Ruhlin consulted her SLHS professors, who also worked with her schedule to ensure that she could be at home with her father around the time of the surgery.

“The SLHS program was so supportive prior to the surgery and during the surgery,” she said. “I could just tell them my dad had an acoustic neuroma, and they knew exactly what it was. I didn’t have to explain anything, and they still ask me how he’s doing. The support from the SLHS faculty, especially being thousands of miles away, I couldn’t be happier to be a part of this program.”

Krishnamurti said what really sets Rachel apart from her peers is that she had the conviction to immediately apply what she learned in class, from the first hearing test through treatment.

“All credit goes to Rachel because she was conscientious, she listened in class, she wrote it down and went home and took her father to the doctor,” Krishnamurti said. “She made sure that he went to one of the best places in the world and got the best treatment, and I’m sure he’s a lot happier man today. It’s heartening for us as faculty members that we were able to give her the information she needed to do the right things.”

Despite some of her professors’ encouragement to pursue audiology, Ruhlin still looks forward to becoming a speech-language pathologist who works with Spanish-speaking families. She said this experience has given her a new appreciation for audiology.

“A lot of times, you learn something in the classroom and you just kind of leave it in the classroom, but it was so impactful that I was able to apply it to something so meaningful in my life,” Ruhlin said. “This will have an impact for years and years, because now the tumor’s gone and he’ll be fine. What I learned potentially saved his life.”